方外:圖寫非人

Beyond the Bounds: Figuring the Nonhuman

文|沈裕昌

By Shen Yu-Chang

什麼是「人物畫」?從字面上來看,人物畫泛指以「人物」作為描繪題材的一類繪畫,是以「題材」作為繪畫分類與命名邏輯的思維產物。然而,此一題材的出現及其邊界,卻並不如表面所見那般理所當然。「人」對於「物」的描繪多止於「窮形」,但是對於「人」的描繪卻務求「盡神」。「人」為何要描繪自身?又如何去描繪自身?這些問題,必然將我們的思考,引向對於「人」之本質的界定。然而,什麼是「人」?作為現代生物分類學的奠基人,林奈(Carl von Linné)在《自然體系》(Systema Naturae)中並沒有為「人」尋得可資辨識的專門特徵,只重述了那句古老的哲學格言:「認識你自己」(nosce te ipsum)。然而「人」之所以必須將自己「認識為人」,卻是為了「成為人」。阿甘本(Giorgio Agamben)在《敞開:人與動物》(L' aperto: L'uomo e l'animale)中指出,「人」為了「成為人」,必須在「非人」當中辨識出自己。但是因為人既沒有本質,也沒有特殊的使命,因此「人」在構成上就是「非人」。

What is figure painting? At first glance, it appears to be a genre defined by subject matter, namely works depicting the “human figure.” Yet the emergence and boundaries of this category are far from self-evident. Depictions of “objects” often pursue external likeness, but portrayals of “people” seek nothing less than the evocation of spirit. Why must humans depict themselves, and how should they do so? Such questions inevitably direct our thinking toward the very nature of the “human.”

Carl von Linné, founder of modern taxonomy, in his Systema Naturae, identified no specific feature to define humanity, other than restating the ancient maxim: nosce te ipsum— “know thyself.” Yet humanity must know itself as human precisely in order to become human. As Giorgio Agamben argues in The Open: Man and Animal, to “become human” one must recognize oneself within the nonhuman. But since humanity has neither an essence nor a special mission, the human is in its very constitution already nonhuman.

然而,「人將自己認識為人,並使自己成其為人」的「認識」與「成為」,具體而言究竟意味著什麼呢?對於海德格(Martin Heidegger)《語言的本質》(Das Wesen der Sprache)而言,或許意味著「語言」與「死亡」。對於漢斯.約納斯(Hans Jonas)《工具、圖像與墳墓:論人身上超越動物性的部分》(Tool, Image, and Grave: On What is Beyond the Animal in Man)而言,則或許意味著「圖像」與「死亡」。奧維德(Publius Ovidius Naso)《變形記》(Metamorphoseon)提到,水澤仙女利里俄珀(Liriope)向先知忒瑞西阿斯(Tiresias)詢問其相貌俊美的孩子納西瑟斯(Narcissus)是否能夠安享天年,先知的答覆是:「是的,如果他永遠不認識自己。」先知的預言,彷彿是德爾斐神諭(Delphi Oracle)的補述。「死亡」與「自我意識」如影隨形。而正如回聲仙女艾可(Echo)與納西瑟斯神話所示,「語言」與「圖像」不只是「認識你自己」的媒介,更是「人將自己認識為人,並使自己成其為人」的行動本身。

But what does it mean, in concrete terms, to “know oneself as human” and thereby “become human”? For Martin Heidegger (The Nature of Language), this may point to language and death; for Hans Jonas (Tool, Image, and Grave), it is image and death. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the nymph Liriope asks the seer Tiresias whether her handsome son Narcissus will live to old age. The seer replies: “Yes, if he never knows himself.” This prophecy seems like an extension of the Delphic oracle. Here, self-consciousness and death shadow one another, inseparable. And as the myth of Echo and Narcissus demonstrates, “language” and “image” are not merely media of self-knowledge but the very acts through which humanity comes to recognize itself as human and to become human.

值得注意的是,正如「死亡」通過想像「我」的消亡,間接地意識到並指認出「我」的存在;「語言」與「圖像」也是通過描繪「非人」,間接地意識到並指認出「人」的存在。奧德修斯(Odysseus)從特洛伊返航途中,被囚禁在食人的獨眼巨人波呂斐摩斯(Polyphemos,有「著名的」之意)的山洞中,當波呂斐摩斯詢問奧德修斯的名字時,他謊稱自己叫做「無人」(Outis)。「人」在「語言」中遇到「著名」的「非人」,通過自稱為「無人」,間接地告訴我們:「人」即是那能通過「語言」以「否定自己的存在」的方式來「肯定自己的存在」的存在。巴塔耶(Georges Bataille)在《藝術的誕生:拉斯科奇蹟》(Lascaux ou la naissance de l'art)中指出,拉斯科洞窟壁畫中的「動物形象都是奇妙的、寫實的」,但是「拉斯科人並不願畫下自己的臉,即使承認自己的人類形態,他們也會在頃刻間將其藏匿起來——彷彿每每想要指明自身的時候,他們就會立刻戴上屬於別人的面具」,且「一旦要描繪人類本身,他們就會將自己的特徵隱藏在動物面具之後。」「人」在「圖像」中遇到「形象鮮明」的「非人」,通過將自己描繪為「戴上動物面具的人」,同樣間接地告訴了我們:「人」即是那能通過「圖像」以「否定自己的存在」的方式來「肯定自己的存在」的存在。「語言」、「圖像」與「死亡」,皆屬於阿甘本所謂的「否定之地」(luogo della negatività)。

Death, language, and image all operate through negation: by imagining the disappearance of the self, death makes the existence of the self perceptible; by depicting the nonhuman, language and image render the human visible. On his return from Troy, Odysseus was trapped in the cave of the man-eating Cyclops Polyphemus—whose name means “famous.” When asked his name, Odysseus answered “Outis,” meaning “Nobody.” In language, the human confronts the “famous” nonhuman, and by calling himself “Nobody” indirectly reveals this truth: humanity is precisely that being which can affirm its existence by negating it through language. Georges Bataille, in Lascaux or the Birth of Art, noted that while the animals in the cave paintings were marvelously realistic, the humans refused to depict their own faces. Even when they acknowledged their human form, they immediately concealed it— as if whenever they tried to show themselves, they had to don the mask of another. Whenever they painted humanity, they hid human features behind animal masks. In images, then, humanity encounters the vividly rendered nonhuman, and by portraying itself as “the one wearing an animal mask,” conveys the same truth: humanity is that being which can affirm its existence by negating it through image. Language, image, and death together constitute what Agamben terms the luogo della negatività—the place of negativity.

就此而言,我們似乎再也不能僅只將「人物畫」單純地視為「繪畫」之中的一個「題材」分類,而應將其理解為「人」通過「圖像」來「將自己認識為人,並使自己成其為人」的行動本身。弔詭的是,人若欲「將自己認識為人,並使自己成其為人」,卻需先「否定人的存在」,繼而才能通過「自由地塑造人的存在」來「肯定人的存在」。正如在最原初的「圖像」之中,「人」既沒有自己的面容,也沒有自己的特徵,因此必須通過「非人」來形構「人」。正是在「圖像」中通過「否定人的面容」以「自由地塑造人的面容」成為「跨人類存在」,「人」才能夠辨識出自己的面容。從拉斯科洞窟壁畫的獸首人物,到埃及神話的獸首神祇;從紅山文化的獸首神人,到三皇傳說中炎帝神農氏的牛首人身,我們可以看到歐亞大陸上最原初的「人形圖像」,皆是「跨人類存在」的「非人圖像」。即便在人文主義(Humanism)的概念萌芽之後,「非人圖像」的創造也未嘗中斷。

From this perspective, figure painting can no longer be regarded simply as one genre among others. Rather, it should be understood as an act through which humanity comes to know itself as human and makes itself human—yet only by first negating its own existence, and then freely reshaping that existence in order to affirm it. In the earliest images, the human had neither its own face nor its own features, and thus had to construct its likeness through the nonhuman. It is precisely by negating the human visage and freely remaking it that humanity appears as a transhuman existence, able to recognize its own face. Across Eurasia, from the masked figures of Lascaux to the animal-headed gods of Egypt, from the hybrid beings of Hongshan culture to the ox-headed body of Shennong in Chinese legend, the earliest human images were all nonhuman figures of transhuman existence. Even after the rise of Humanism, the creation of such nonhuman imagery never ceased.

《宣和畫譜》將宋徽宗時期宮廷內府藏畫依照題材分為十門,位列於首者即「道釋」、「人物」二門。〈道釋敘論〉「藝也者,雖志道之士所不能忘,然特游之而已。畫亦藝也,進乎妙,則不知藝之為道,道之為藝」,「於是畫道釋像與夫儒冠之風儀,使人瞻之仰之,其有造形而悟者,豈曰小補之哉?」可知「道釋」所欲描繪者,實非「偶像」,而是使人「瞻仰」之「風儀」。繪者藉此以「藝」游於「道」,更使觀者由「形」而悟「道」。〈人物敘論〉則指出「故畫人物最為難工,雖得其形似則往往乏韻」,大多「皆是形容見於議論之際而然也」,但「若夫殷仲堪之眸子,裴楷之頰毛,精神有取於阿堵中,高逸可置之丘壑間者,又非議論之所能及,此畫者有以造不言之妙也。」可知「人物」描繪的重點並非「形似」,而是「精神」、「高逸」等「非議論所能及」的「神」、「韻」之呈現。由此可見,「道釋」、「人物」所描繪者皆非一般意義上的「人」,而是「人」逸出其自身的「非人」狀態。就此而言,我們似乎唯有通過不同時代的「非人圖像」,才得以照見該時代的「人之面容」,並從中領會其「時代精神」。

The Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings, compiled under Emperor Huizong, divided the imperial collection into ten categories, with “Daoist and Buddhist subjects” and “figures” placed at the forefront. The commentary on Daoist and Buddhist subjects makes clear that these were not mere idols, but representations of bearing and spirit—images through which viewers could look up, contemplate, and, by engaging with form, attain an understanding of the Dao. Here, art and Dao were seen to flow into one another: when art reaches the level of the marvelous, one no longer knows whether art is Dao or Dao is art. The section on figure painting likewise notes that likeness alone often falls flat; what matters is the capture of spirit and character, qualities beyond verbal argument. The eyes of Yin Zhongkan or the delicate hair on Pei Kai’s cheeks were cited as examples of details that reveal spirit and lofty grace, things that cannot be grasped through discourse alone but only through painting. Thus, both Daoist-Buddhist and secular figures aimed not at mere resemblance but at presenting spirit, vitality, and transcendence. What they depict is never simply “the human” in the ordinary sense, but humanity as it moves beyond itself into the nonhuman. In this light, it is only through the nonhuman images of different eras that we glimpse the human face of that era and discern its particular spirit of the age.

楊寓寧使用連筆、宿墨與生紙,通過強烈的筆觸與帶有顆粒感的墨色變化,描繪聖母瑪利亞(Ave Maria)與聖塞巴斯提安(St. Sebastian)等基督教聖像主題。清透但烏黑的宿墨,在寬幅筆具的拖曳之下,形成周折且連貫的帶狀線條,用以描繪聖母與聖人衣袍,創造出如縐紗般輕盈飄揚的褶疊質地。

Yang Yu-Ning employs cursive brushwork, overnight ink and Sheng Xuan (Raw Xuan Paper) to render Christian saints such as the Ave Maria and St. Sebastian. The transparent yet dense black of the overnight ink, drawn with broad brushstrokes, forms winding but continuous bands of lines that depict the robes of the Virgin and the saint, creating folds that appear light and flowing, like fine gauze.

郭輝選擇絹本設色,運用纖密沈著的工筆線條,輔以墨色為基礎的淡雅色彩進行烘染,重新詮釋了臥佛、羅漢、僧伽等經典的佛教繪畫題材。羅漢、僧伽的衣袍,因為使用如山巒起伏般連綿堆疊的短弧狀線條,與沿著輪廓線而施的漸次分染,而表現出豐軟且厚實的蓬鬆量體感。兩者就題材而言則一耶一釋,就技法而言則一寫一工,就媒材而言則一墨一彩,在「神人」主題中構成一組有趣的對比。

Guo Hui works on silk with color, employing precise and deliberate gongbi linework, complemented by subtle washes of ink-based tones, to reinterpret classic Buddhist subjects such as the Reclining Buddha, arhats, and monks. The robes of the arhats and monks are rendered with short, arching lines layered like mountain ridges, combined with gradual shading along the contours, creating a soft yet substantial sense of volume and fullness. They differ in subject—Christianity and Buddhism, in technique—expressive brushwork and meticulous gongbi line, and in medium—monochrome ink and color. Together, these differences create a striking dialogue within the theme of “Deities”.

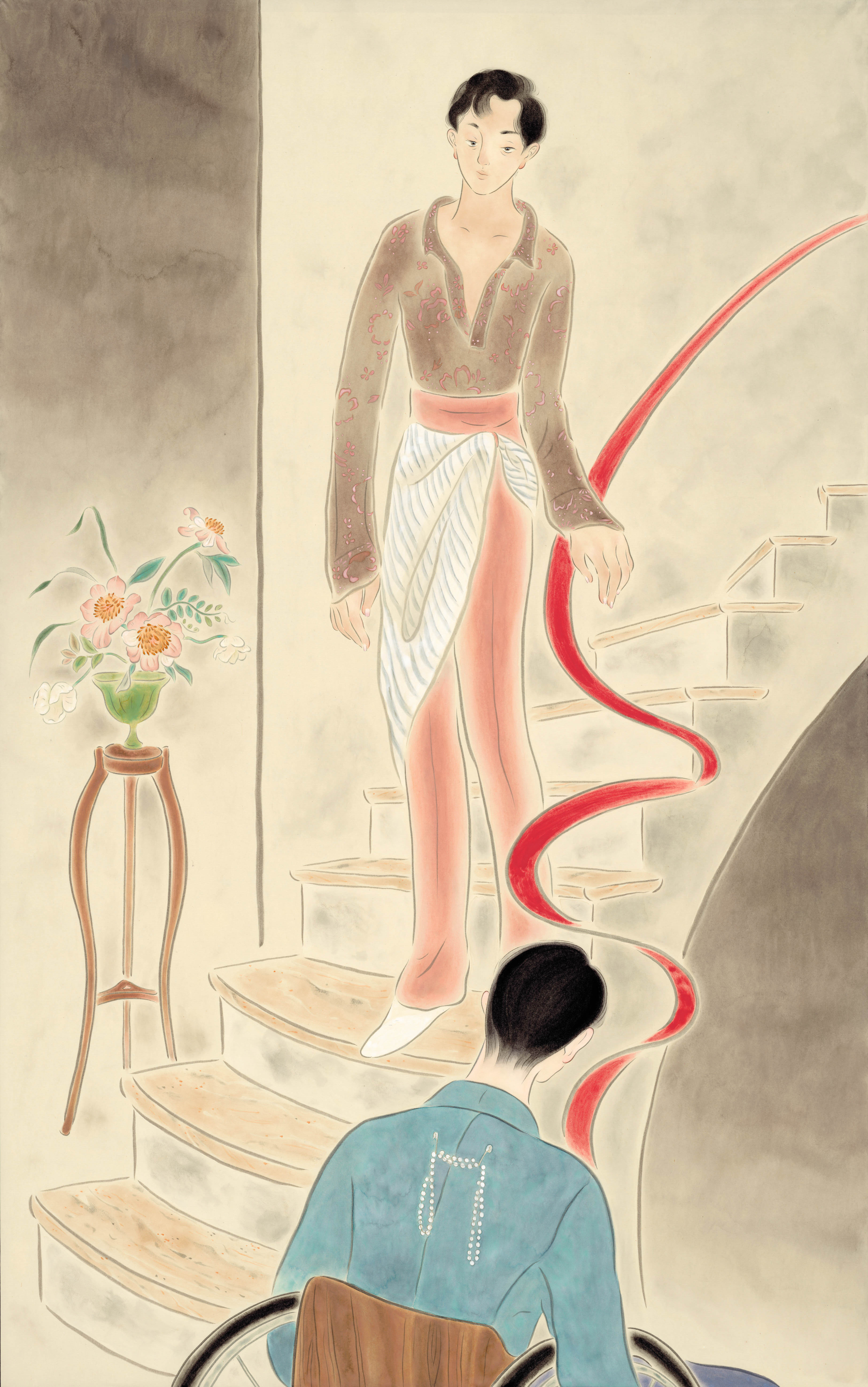

花季琳亦使用淡雅的紙本設色,但是更加偏好鬆緩柔軟的線條,配合從塊面中央向四周暈塗的染法,不只能使墨線與色兩不相礙,更能在量體感與氛圍之間進行曖昧的調度。畫面通過帶有寓意的物件與紋樣,創造出可閱讀的大量細節,藉以描繪帶有故事性意涵的場景。主題則多行止從容而有幽思之神貌,且為情愛所困的「佳人」。

Hua Ji-Lin also works with subtle color on paper, favoring relaxed and supple lines combined with washes that fade outward from the center of each form. This approach allows ink lines and color to coexist without conflict, while balancing volume and atmosphere in a deliberately ambiguous way. Her compositions incorporate symbolic objects and patterns that generate abundant detail for the viewer to read, constructing scenes with narrative implications. The figures are often “Fair Maidens”, portrayed with a contemplative presence yet caught in the entanglements of love.

顏妤庭在近期的創作中,先使用筆具與墨在紙上抄寫新聞內容,創造出滿佈可識讀文字的畫面肌理,再於其上描繪被捆縛、擠壓、擰轉、扭絞得不成人形,且不具有個人面貌的無名人物。這些無名之人,皆是在經濟與科技的強勢發展和訊息的高速流通中,遊走在實體世界的交通網絡與虛擬世界的資訊網絡之間的「遊子」。

Yen Yu-Ting, in her recent work, begins by copying news texts onto paper with brush and ink, creating a surface densely covered with legible words. Over this ground she paints nameless figures—bodies bound, compressed, twisted, and distorted beyond recognition, stripped of individual features. These anonymous beings represent “Wanderers” caught between the physical networks of transportation and the virtual networks of information, moving through a world shaped by rapid technological and economic forces.

潘信華先在紙面上營造出質地斑駁的肌理並染上古色,再於其上描繪在臺灣各地行旅時所見的特殊地貌與地方物種,畫面正中央則經常佇立著一位光頭、著衣、赤足,有時未著褲的「童子」。

Pan Hsin-Hua first creates mottled textures on paper, staining them with an antique tone. Upon this surface he paints distinctive landscapes and local species encountered during his travels across Taiwan. At the center of these compositions, a bald, clothed, barefoot—and at times partially unclothed— “Divine Child” often stands in quiet presence.

于彭以帶有狂草或速寫般的率性筆法描繪的山水與園林中,亦常出現赤身的「裸女」與垂髫的「童子」。然而,潘信華畫中的「童子」年紀更小,多不帶表情地兩眼圓睜凝視著觀者,最初帶有玩世諧謔的意味。于彭畫中的「童子」則年齡稍長,時而恍惚低眉、時而悵然閉目,雖是以其子入畫,亦讓人聯想到《老子》「為天下谿,常德不離,復歸於嬰兒」的想望。此外,于彭畫中的「童子」,有時亦與「佳人」相為伴,或如「遊子」自放於曠野。

In Yu Peng’s landscapes and gardens, painted with a spontaneous brushwork reminiscent of wild cursive script or quick sketches, nude female figures and young divine children frequently appear. By contrast, the divine child in Pan Hsin-Hua’s work is younger, staring wide-eyed and expressionless at the viewer, initially with a sense of playful irreverence. Yu Peng’s divine child figures are slightly older, sometimes lowering their gaze in a trance or closing their eyes in melancholy. Although based on his own son, they evoke the Daoist ideal described in the Dao De Jing: “to be the valley of the world, to remain constant in virtue, and to return to the state of the infant.” At times, Yu Peng’s divine children accompany the fair maiden, or, like wanderers, release themselves into the open landscape.

《莊子》〈大宗師〉謂超逸於世之人為「遊方之外者」,展覽故題名「方外:圖寫非人」,並分為「神人」、「佳人」、「遊子」、「童子」四個子題,邀請于彭、花季琳、郭輝、楊寓寧、潘信華、顏妤庭六位當代書畫創作者在「異雲書屋」的「金華館」與「青田館」參與展出。「青田館」展出「神人」(楊寓寧、郭輝)、「佳人」(花季琳、于彭),「青田館」則展出「遊子」(顏妤庭、于彭)、「童子」(潘信華、于彭)。展覽也邀請觀者親臨現場,觀看作品中描繪的「非人圖像」,與創作者們一同塑造當代的「人之面容」。

In the chapter “The Great Master” of the Zhuangzi, those who transcend the ordinary world are described as “wanderers beyond the bounds.” It is from this idea that the exhibition takes its title, Beyond the Bounds: Figuring the Nonhuman, organized into four sub-themes: Deities, Fair Maidens, Wanderers, and Divine Children. The exhibition brings together six contemporary painters and calligraphers—Yu Peng, Hua Ji-Lin, Guo Hui, Yang Yu-Ning, Pan Hsin-Hua, and Yen Yu-Ting—across Yi Yun Art’s Jinhua and Qingtian spaces. The Qingtian space presents Deities (Yang Yu-Ning, Guo Hui) and Fair Maidens (Hua Ji-Lin, Yu Peng), while the Jinhua space features Wanderers (Yen Yu-Ting, Yu Peng) and Divine Children (Pan Hsin-Hua, Yu Peng). Visitors are invited to encounter the “nonhuman images” portrayed in these works and, together with the artists, reflect on how the face of humanity is shaped today.

%EF%BC%8C%E6%B0%B4%E5%A2%A8%E8%A8%AD%E8%89%B2%E7%B4%99%E6%9C%AC%20Ink%20and%20color%20on%20paper%EF%BC%8C65%20x%2043%20cm%EF%BC%8C1992_%E7%B6%B2%E9%A0%81%E7%94%A8.webp)